A team of medical professionals engaged in a surgical procedure in an Operation Room in SIUT, Karachi. Picture by Kohi Marri.

Beyond curing Maladies: Reflections of a Liver Transplant Surgeon

Muhammad Arsalan Khan*

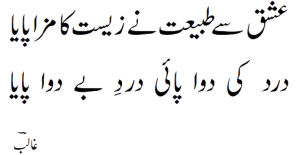

Through passion, my disposition discovered the flavors of life

I found pain with remedies and sufferings with none.

Ghalib (translation by the editor)

I work at a public hospital in Pakistan that provides all medical services, including organ transplantation, free of charge, made possible through government funding and private donations. The hospital serves a large number of underprivileged individuals from all across the country. Limited resources of most families adds to the responsibilities of the liver transplant team. These include carefully weighing the benefits of transplanting the patient, and potential risks to the donor along with the repercussions for large, interdependent families.

Transplant surgeons and coordinators must often delve deep into personal matters of the donor and recipient and their family leading to long-term relationships that begin well before the actual transplant takes place. We inquire about the size of their homes and living arrangements, the number of family members, income levels of breadwinners, quality of their water supply, and access to sufficient food. We understand that our technological success is dependent at least as much on their socioeconomic milieu as it is on the biological fitness of donor and recipient. Patients often draw us into their lives, akin to “elders” of the family, for matters extending beyond their physical maladies. And some of these stories remain indelible in my mind.

For young Talha, our hospital became a refuge from a broken family. A year after his mother generously donated her liver for his transplant, his parents divorced amid a bitter dispute. His mother remarried and moved away. His father, who had custody, had to leave for long trips for his job as a truck driver. Talha mostly lived with his Chacha’s (paternal uncle) family, facing hardships from his uncle’s wife, who treated him like a servant. Whenever he felt overwhelmed, he would come to the hospital, as he knew we would admit him for a “workup” for his symptoms. This way he could stay in the hospital until his father returned and took him home.

After his father died in a tragic truck accident, Talha’s visits grew infrequent, until one day, gravely ill, he was brought once more to the hospital. He was severely dehydrated and in shock, reportedly suffering from diarrhea for a few days. We suspected he had been ill much longer. Despite our efforts, we were unable to save Talha. The technological success of the complex medical process was eclipsed by the social vagaries that had befallen this troubled young man.

Sana, a young teenager pleaded to us, “Doctor sahib, can you please tell my father to pay attention to us too, not just his new wife.” She had received a liver transplant from her older brother a couple of years ago. She expressed frustration that her father, who had separated from her mother and remarried a younger woman, had neglected her and their household needs. We were surprised since we had known him to be a caring and involved father. This request left us a little overwhelmed due to the weight of expectations placed on us. My colleague and I nodded as we left the clinic’s cubicle. We made attempts to contact the father but received no response. Her request however seemed natural to us. After all we had allowed the family to make us a part of their lives over the years.

These stories of real people in the real world are glimpses into our everyday experiences as transplant surgeons. For me, the couplet by Ghalib, the most celebrated Urdu poet of all times, offers a reflection of our pursuit in alleviating the suffering of our patients and their families. We don’t always succeed, but the essence is in the effort. That makes it worth it, every time.